“Talking about bicycles,” said my friend, “I have been through the four ages. I can remember a time in early childhood when a bicycle meant nothing to me: it was just part of the huge, meaningless background of grown-up gadgets against which life went on. Then came a time when to have a bicycle, and to have learned to ride it, and to be at last spinning along on one’s own, early in the morning, under trees, in and out of the shadows, was like entering Paradise. That apparently effortless and frictionless gliding—more like swimming than any other motion, but really most like the discovery of a fifth element—that seemed to have solved the secret of life. Now one would begin to be happy. But, of course, I soon reached the third period. Pedalling to and fro from school (it was one of those journeys that feel up-hill both ways) in all weathers, soon revealed the prose of cycling. The bicycle, itself, became to me what his oar is to a galley slave.”

“But what was the fourth age?” I asked.

“I am in it now, or rather I am frequently in it. I have had to go back to cycling lately now that there’s no car. And the jobs I use it for are often dull enough. But again and again the mere fact of riding brings back a delicious whiff of memory. I recover the feelings of the second age. What’s more, I see how true they were—how philosophical, even. For it really is a remarkably pleasant motion. To be sure, it is not a recipe for happiness as I then thought. In that sense the second age was a mirage. But a mirage of something.”

“I mean this. Whether there is, or whether there is not, in this world or in any other, the kind of happiness which one’s first experiences of cycling seemed to promise, still, on any view, it is something to have had the idea of it. The value of the thing promised remains even if that particular promise was false—even if all possible promises of it are false.”

“Sounds like a carrot in front of a donkey’s nose”, said I.

“Even that wouldn’t be quite a cheat if the donkey enjoyed the smell of carrots as much as, or more than, the taste. Or suppose the smell raised in the donkey emotions which no actual eating could ever satisfy? Wouldn’t he look back (when he was an old donkey, living in the fourth age) and say, I’m glad I had that carrot tied in front of my nose. Otherwise I might still have thought eating was the greatest happiness. Now I know there’s something far better—the something that came to me in the smell of the carrot. And I’d rather have known that—even if I’m never to get it—than not to have known it, for even to have wanted it is what makes life worth having’.”

“I don’t think a donkey would feel like that at all.”

“No. Neither a four-legged donkey nor a two-legged one. But I have a suspicion that to feel that way is the real mark of a human.”

“So that no one was human till bicycles were invented?”

“The bicycle is only one instance. I think there are these four ages about nearly everything. Let’s give them names. They are the Unenchanted Age, the Enchanted Age, the Disenchanted Age, and the Re-enchanted Age. As a little child I was Unenchanted about bicycles. Then, when I first learned to ride, I was Enchanted. By sixteen I was Disenchanted and now I am Re-enchanted.”

“Go on”, said I. “What are some of the other applications?”

“I suppose the most obvious is love. We all remember the Unenchanted Age—there was a time when women meant nothing to us. Then we fell in love; that, of course, was the Enchantment. Then, in the early or middle years of marriage there came—well, Disenchantment. All the promises had turned out, in a way, false. No woman could be expected—the thing was impossible—I don’t mean any disrespect either to my own wife or to yours. But—”

“I was never married”, I reminded him.

“Oh! That’s a pity. For in that case you can’t possibly understand this particular form of Re-enchantment. I don’t think I could explain to a bachelor how there comes a time when you look back on that first mirage, perfectly well aware that it was a mirage, and yet, seeing all the things that have come out of it, things the boy and girl could never have dreamed of, and feeling also that to remember it is, in a sense, to bring it back in reality, so that under all the other experiences it is still there like a shell lying at the bottom of a clear, deep pool—and that nothing would have happened at all without it—so that even where it was least true it was telling you important truths in the only form you would then understand—but I see I’m boring you.”

“Not at all”, said I.

“Let’s take an example that may interest you more. How about war? Most of our juniors were brought up Unenchanted about war. The Unenchanted man sees (quite correctly) the waste and cruelty and sees nothing else. The Enchanted man is in the Rupert Brooke or Philip Sidney state of mind—he’s thinking of glory and battle-poetry and forlorn hopes and last stands and chivalry. Then comes the Disenchanted Age—say Siegfried Sassoon. But there is also a fourth stage, though very few people in modern England dare to talk about it. You know quite well what I mean. One is not in the least deceived: we remember the trenches too well. We know how much of the reality the romantic view left out. But we also know that heroism is a real thing, that all the plumes and flags and trumpets of the tradition were not there for nothing. They were an attempt to honour what is truly honourable: what was first perceived to be honourable precisely because everyone knew how horrible war is. And that’s where this business of the Fourth Age is so important.”

“Isn’t it immensely important to distinguish Unenchantment from Disenchantment—and Enchantment from Re-enchantment? In the poets for instance. The war poetry of Homer or The Battle of Maldon, for example, is Re-enchantment. You see in every line that the poet knows, quite as well as any modern, the horrible thing he is writing about. He celebrates heroism but he has paid the proper price for doing so. He sees the horror and yet sees also the glory. In the Lays of Ancient Rome, on the other hand, or in Lepanto (jolly as Lepanto is) one is still enchanted: the poets obviously have no idea what a battle is like.1 Similarly with Unenchantment and Disenchantment. You read an author in whom love is treated as lust and all war as murder—and so forth. But are you reading a Disenchanted man or only an Unenchanted man? Has the writer been through the Enchantment and come out on to the bleak highlands, or is he simply a subman who is free from the love mirage as a dog is free, and free from the heroic mirage as a coward is free? If Disenchanted, he may have something worth hearing to say, though less than a Re-enchanted man. If Unenchanted, into the fire with his book. He is talking of what he doesn’t understand. But the great danger we have to guard against in this age is the Unenchanted man, mistaking himself for, and mistaken by others for, the Disenchanted man. What were you going to say?”

“I was just wondering whether the Enchantment which you claim to look back on from the final stage was often no more than an illusion of memory. Doesn’t one remember a good many more exciting experiences than one has really had?”

“Why yes. In a sense. Memory itself is the supreme example of the four ages. Wordsworth, you see, was Enchanted. He got delicious gleams of memory from his early youth and took them at their face value. He believed that if he could have got back to certain spots in his own past he would find there the moment of joy waiting for him. You are Disenchanted. You’ve begun to suspect that those moments, of which the memory is now so ravishing, weren’t at the time quite so wonderful as they now seem. You’re right. They weren’t. Each great experience is

‘a whisper

Which Memory will warehouse as a shout.’2

But what then? Isn’t the warehousing just as much a fact as anything else? Is the vision any less important because a particular kind of polarized light between past and present happens to be the mechanism that brings it into focus? Isn’t it a fact about mountains—as good a fact as any other—that they look purple at a certain distance?—If you won’t have any more beer perhaps we’d better be getting along. That man on the other side of the bar thinks we’ve been talking politics.”

“I’m not sure that we haven’t”, said I.

“You’re quite right. You mean that Aristocracy is one other example? It was the merest Enchantment to suppose that any human beings, trusted with uncontrolled powers over their fellows, would not use it for exploitation; or even to suppose that their own standards of honour, valour, and elegance (for which alone they existed) would not soon degenerate into flash-vulgarity. Hence, rightly and inevitably, the Disenchantment, the age of Revolutions. But the question on which all hangs is whether we can go on to Re-enchantment.”

“What would that Re-enchantment be?”

“The realization that the thing of which Aristocracy was a mirage is a vital necessity; if you like, that Aristocracy was right: it was only the Aristocrats who were wrong. Or, putting it the other way, that a society which becomes democratic in ethos as well as in constitution is doomed. And not much loss either.”

Notes

- The Battle of Maldon, a poem in Old English of the tenth century, is about the raid of the Northmen under Anlaf, at Maldon in Essex, in 991. The Lays of Ancient Rome (1842) are by Thomas Macaulay, and Lepanto (1911) is by G.K. Chesterton.

- From an unpublished poem by Owen Barfield.

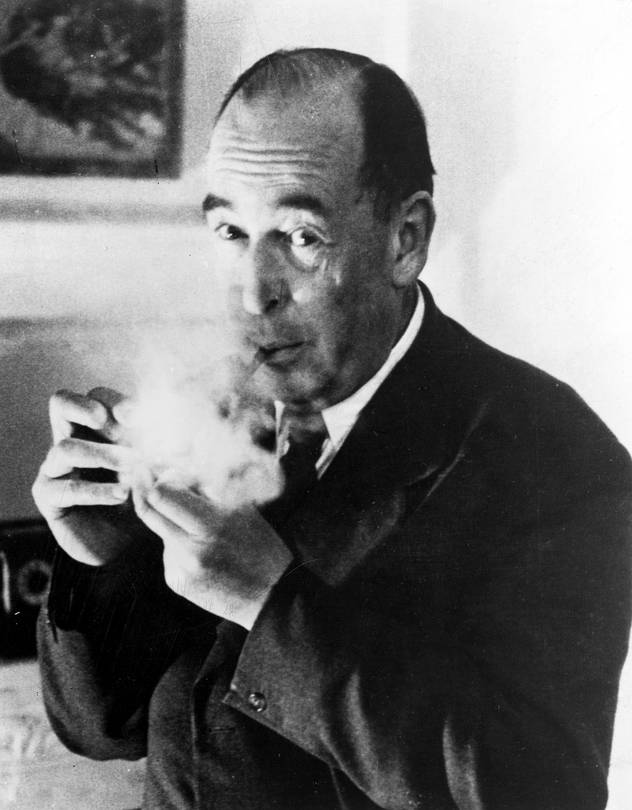

2 thoughts on “Talking about Bicycles by C. S. Lewis”